Tags

12-21-12, Art Deco, Art Pottery, Aztec calendar, Fauquier Appraisers, fine art appraisals, Frank Lloyd Wright, Frankoma, Martha Stewart, Mayan calendar, Mayan Revival Style, Mayan-Aztec, Robert Stacy-Judd, Stephen Catherwood

There’s a lot of internet chatter about the upcoming end of the world predicted by the ancient Maya calendar. Of course, the Maya cosmos “ended” every 52 years –a span called a katun — but that’s another story. Accompanying these dire internet predictions is usually an illustration of an ancient stone calendar. Problem is, it’s almost always the Aztec sun calendar, not a Maya artifact at all.

ABC2news’ article “NASA says world won’t end in 2012 despite Mayan calendar” featured this image…of an Aztec sun calendar.

This may be graduate-school niggling on my part but it’s germane to today’s post in a couple of important ways. Most notably in that this dual fascination and confusion over Aztec versus Maya is nothing new, as demonstrated by an art form that has become a little obsession with me: Mayan Revival design.

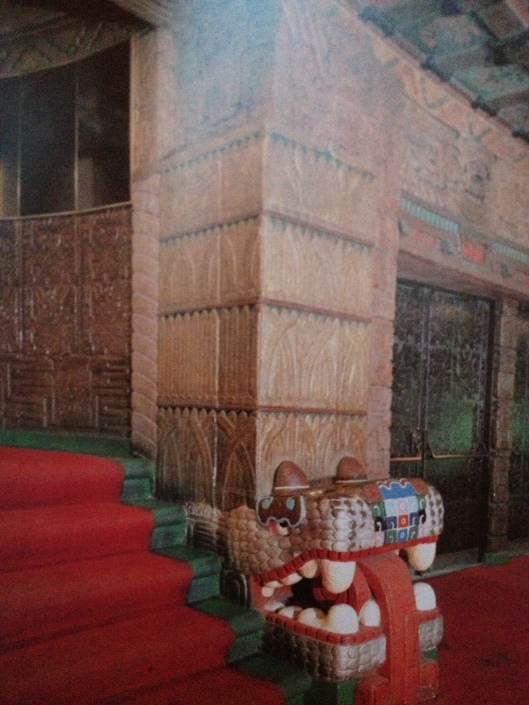

The Mayan Revival architectural style flourished through the 1920s and 30s, promulgated by major architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and lesser ones like Robert Stacy-Judd. Southern California, in particular, is studded with surviving Mayan Revival architecture, from the Aztec Hotel in Monrovia (whose source is in fact primarily Mayan) to the Mayan Ballroom in downtown LA (whose motifs are largely Aztec).

The (Aztec inspired) Mayan Ballroom and Frank Lloyd Wright’s celebrated Ennis House are outstanding examples of the Mayan Revival style.

And although it’s generally thought of as a subset of Art Deco, Mayan Revival design endured in the decorative arts through World War II and into the 1950s. I have long suspected that this is owing in part to the marketing skill of retailers like Stanley Marcus (of Neiman-Marcus fame), who, needing something fresh and alluring to sell when the war cut off access to many European imports, turned to the Americas for inspiration. Peasant skirts, Frida Kahlo headdresses, Taxco silver, Spanish colonial architecture, and a general interest in Latin American art and culture–high and low–exploded. Ever seen Walt Disney’s Three Caballeros? It’s basically an extended travel brochure from the 1940s.

Frankoma Pottery was a latecomer to the Mayan Revival aesthetic, but the line of tableware known as “Maya-Aztec” are among the genre’s most charming and enduring examples. I first learned about them in a Martha Stewart Living article: I was in the middle of writing a graduate research paper called something pretentious like “Gringo Appropriations of Pre-Colombian Cosmological Glyphs” when I stumbled on Stewart’s description of her own collection of Frankoma dishes. As luck would have it, the next week I almost tripped over a complete service for eight in a local junk shop and, scraping together the last pennies of my meager TA’s stipend, appropriated my very own slice of Mayan Revival design.

Frankoma’s Maya-Aztec pattern is loosely based on glyphs of the kind discovered in the late 19th century at Palenque in Southern Mexico. These were extensively published throughout the first quarter of the 20th century and would have been easily available as source material for Frankoma’s founder and lead designer, John Nathaniel Frank. Prior to embarking on pottery making as a full-time career, Frank had worked at the University of Oklahoma at Norman, which owns one of the finest collections of Pre-Colombian archives in the United States. I don’t know but have always suspected that this would have been where Frank became acquainted with photos and drawings from the Palenque excavation that became the source for his designs.

Frankoma’s Aztec-Maya pattern was used on dinner plates, serving dishes, platters, gravy boats, butter dishes and just about anything else you might set on a table at dinner time. They come in Frankoma’s signature earthy glazes Prairie Green and Desert Gold, and are extremely durable. I have used mine nearly every day for the past 18 years and have not lost a piece yet.

So when 12-21-12 rolls around, we’ll be enjoying an end-of-katun feast on a table set, appropriately, with Mayan Revival dishes. And in another 52 years we’ll probably do it again.

Hasn’t the Ennis house been in a few Hollywood movies as well – love your dishes!